Response

Too Late: Why Most Abortion Pill Administrative Procedure Challenges Are Untimely

Susan C. Morse & Leah R. Butterfield *

A Note for Readers:

In this Response, Susan C. Morse & Leah R. Butterfield discuss David S. Cohen, Greer Donley & Rachel Rebouché’s recent Stanford Law Review Article Abortion Pills. Cohen et al.’s Article can be found here.

* * *

Introduction

In Abortion Pills, Professor David Cohen, Professor Greer Donley, and Dean Rachel Rebouché argue that abortion pills are here to stay. 1 See generally, David S. Cohen, Greer Donley & Rachel Rebouché, Abortion Pills, 76 Stan. L. Rev. 317, 322 (2024) (noting the current accessibility of abortion pills). Medication abortion already has transformed access to abortion and shifted control to patients and “abortion providers and activists.” 2 Id. Their Article emphasizes the value of stability, meaning continued access to medication abortion, in existing reproductive rights law.

Their Article also explains that the Supreme Court is considering a case that would upend the legal status quo that Abortion Pills describes. This term, the Court will review the Fifth Circuit’s decision in Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine v. FDA (AHM). AHM presents administrative procedure challenges to the regulation of mifepristone, a common medication used for abortion, by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 3 All. for Hippocratic Med. v. FDA, 78 F.4th 210, 245-51 (5th Cir. 2023), cert. granted, 2023 WL 8605746 (U.S. Dec. 13, 2023) (No. 23-235) (considering whether 2016 and 2021 actions were arbitrary and capricious).

AHM raises the possibility of abrupt withdrawal of medication abortion access. But there are several legal avenues to resolve AHM without this result. One possibility is the plaintiffs’ lack of standing. 4 See Brief for Federal Appellants at 19-34, All. for Hippocratic Med. v. FDA, 78 F.4th 210 (5th Cir. 2023) (No. 23-10362) (arguing that plaintiffs lack associational, organizational, and third-party standing). Intervenors at the district court also claim to have state standing. See Missouri, Kansas, and Idaho’s Motion to Intervene, at 2-3, All. for Hippocratic Med. v. FDA, No. 2:22-CV-00223-Z, (N. D. Tex. Nov. 3, 2023). Another possibility is the six-year limitations period of 28 U.S.C. § 2401(a). The Fifth Circuit relied on this statute to time-bar the challenge to the FDA’s 2000 approval of mifepristone, 5 All. for Hippocratic Med. v. FDA., 78 F.4th 210, 242 (5th Cir. 2023), cert. granted, 2023 WL 8605746 (U.S. Dec. 13, 2023) (No. 23-235). and it also should have blocked the challenge to actions taken by the FDA in 2016. 6 On 28 U.S.C. § 2401(a) and administrative procedure claims, compare Susan C. Morse, Old Regs: The Default Six-Year Time Bar for Administrative Procedure Claims, 31 Geo. Mason L. Rev.191, 218-227 (2024) (arguing for accrual at the time of agency promulgation or other action), with John Kendrick, Note, (Un)Limiting Administrative Review: Wind River, Section 2401(a), and the Right to Challenge Federal Agencies, 103 Va. L. Rev. 157, 190-92 (2017) (arguing for later accrual for each specific plaintiff).

I. Abortion Pills as Status Quo

As Abortion Pills reveals, misoprostol and mifepristone have transformed the landscape of reproductive health care. 7 See Cohen et al., supra note 1, at 355-80 (detailing telehealth provision, pharmacist prescription, and other strategies to expand access with reduced involvement from medical gatekeepers). Medication abortion has rapidly established a new normal in which patients and “informal and underground networks” have more control over access to abortion services. 8 Id. at 317. Meanwhile, counterattacks come from federal litigation and state regulation, 9 See id. at 333-34. and availability and sanctions vary because of class and race bias in the application of abortion restrictions and bans. 10 See id. at 399-400 (explaining criminalization bias).

Abortion Pills emphasizes the status quo of expanded access, in which medication abortion is more widely available. Law that maintains the status quo often connects to “traditional conservativism.” 11 Edgar Bodenheimer, The Inherent Conservativism of the Legal Profession, 23 Ind. L. J. 221, 227-28 (1948) (arguing that law tends to resist change and restrain “exercise of power by private individuals as well as by the government”); see, e.g., Cristina M. Rodriguez, Foreward: Regime Change, 135 Harv. L. Rev. 1, 103-09 (2021) (noting the anti-progressive status quo of immigration law). But in the case of abortion pills, the value of stability in the law supports, though imperfectly, the progressive goal of reproductive access and freedom. Abortion will be more available if courts leave the FDA rules alone.

The government in AHM has emphasized the doctor plaintiffs’ lack of standing. 12 See supra note 4. But in the Fifth Circuit, a different law has protected the status quo, at least with respect to the FDA’s original 2000 approval of mifepristone. 13 All. for Hippocratic Med. v. Food & Drug Admin., 78 F.4th 210, 242 (5th Cir. 2023), cert. granted, 2023 WL 8605746 (U.S. Dec. 13, 2023) (No. 23-235). See generally Susan C. Morse & Leah R. Butterfield, Out of Time at the Fifth Circuit: Why (Most of) the Mifepristone Challenge in Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine is Time-Barred, Yale J. Reg. Notice & Comment (March 24, 2023), https://perma.cc/6J4C-5JT6 (arguing that 28 U.S.C. § 2401(a) should block claims). This law is 28 U.S.C. § 2401(a), a default six-year limitations period for suits against the federal government. This Essay explores how this limitations period protects the abortion pill status quo—no matter what happens with standing.

A Supreme Court majority might decide AHM in favor of the government based on standing and ignore 28 U.S.C. § 2401(a). 14 See, e.g., Steel Co. v. Citizens for Better Env’t, 523 U.S. 83, 94-95 (1998) (discussing the need to decide jurisdictional issues like standing first before reaching the merits). But any dissenting opinion must consider the limitations period argument before concluding that FDA actions should be invalidated. And getting the limitations period analysis right is important not only in AHM but also in Corner Post, another case on the Supreme Court’s merits docket, in which accrual of the six-year time-bar is the central issue. 15 N. Dakota Retail Ass’n v. Bd. of Governors of Fed. Res. Sys. (Corner Post), 55 F. 4th 634, 639 (8th Cir. 2022), cert granted sub. nom. Corner Post, Inc. v. Bd. of Governors of Fed. Res. Sys., No 22-1008, 2023 WL 6319653, at *1 (U.S. Sept. 29, 2023). In Corner Post, petitioners argue that 28 U.S.C. § 2401(a) accrues when a plaintiff can initiate and maintain a suit in court. See Petition for Writ of Certiorari, at 21-22, Corner Post, No. 22-1008, (U.S. Apr. 13, 2023). The Corner Post petitioner argues that accrual began no earlier than the time of its incorporation in 2017, so that its 2021 challenge to a 2011 Federal Reserve regulation is timely. 16 See Brief for Petitioner, at 8-9, Corner Post, No. 22-1008, (U.S. Nov. 13, 2023) (providing chronology).

II. The Policy of the Six-Year Time Bar

All Courts of Appeals that have considered the issue agree that the six-year time bar of 28 U.S.C. § 2401(a) accrues for administrative procedure claims when a rule is promulgated. 17 See, e.g., Corner Post, 55 F.4th at 637, 639-41 (8th Cir. 2022) (holding time-barred an arbitrary and capricious challenge to a 2011 Federal Reserve regulation); Texas v. Rettig, 987 F.3d 518, 523-24 (5th Cir. 2021) (holding time-barred a notice-and-comment challenge to a 2002 HHS regulation); Alabama v. PCI Gaming Authority, 801 F.3d 1278, 1292 (11th Cir. 2015) (holding time-barred an APA challenge to Secretary of Interior decisions to take lands into trust in 1984, 1992 and 1995); Hire Order Ltd. v. Marianos, 698 F.3d 168, 170 (4th Cir. 2012) (holding time-barred a notice-and-comment challenge to a 1969 Revenue Ruling); Sai Kwan Wong v. Doar, 571 F.3d 247, 263 (2d Cir. 2009) (holding time-barred a notice-and-comment challenge to a 1980 Medicaid regulation); Preminger v. Sec’y of Veterans Affairs, 517 F.3d 1299, 1299, 1307-08 (Fed. Cir. 2008) (holding time-barred a notice-and-comment challenge to a 1973 Veterans Affairs regulation regarding political demonstrations at VA facilities); Harris v. FAA, 353 F.3d 1006, 1009, 1011-13 (D.C. Cir. 2004) (holding time-barred an arbitrary and capricious challenge to a 1993 FAA Notice); Cedars-Sinai Med. Center v. Shalala, 177 F.3d 1126, 1128-29 (9th Cir. 1999) (holding time-barred a notice-and-comment challenge to a 1986 Medicare manual); Trafalgar Cap. Assocs. v. Cuomo, 159 F.3d 21, 34-35 (1st Cir. 1998) (holding time-barred an arbitrary and capricious challenge to a 1985 HUD fair market rent assessment); Sierra Club v. Slater, 120 F.3d 623, 628, 631 (6th Cir. 1997) (holding time-barred a claim brought under NEPA via the APA to a 1984 Federal Highway Administration Record of Decision). The statutory text, the status of administrative procedure as a public right, and reliance interests all support this earlier-accrual result. 18 For additional development of these arguments, see Morse, supra note 6, at 218-27.

First, consider the statutory text. It’s clear that APA claims must be timely. The APA provides that claims cannot be made when a limitations period “precludes judicial review.” 19 5 U.S.C § 701(a)(1). In the absence of any more specific limitations period, 28 U.S.C. § 2401(a) states that the six-year clock starts ticking when “the right of action first accrues.” 20 28 U.S.C. § 2401(a).

The APA clarifies the time of accrual by identifying the “unlawful” event as the “agency action . . . found to be without observance of procedure required by law.” 21 5 U.S.C. § 706(2)(D); see also 5 U.S.C. § 706(2)(A) (identifying the unlawful act or an agency’s arbitrary or capricious action). The moment of administrative procedure illegality is the moment “without observance of procedure,” which must be when the agency promulgates a regulation or issues a rule. Consider a claim of inadequate notice and comment, or a claim of an arbitrary and capricious process that failed to consider all evidence, adequately respond to comments, or sufficiently explain a regulatory change. In each of these cases, the transgression is complete when the agency promulgates the rule. The claim is available to all eligible plaintiffs on the same basis at that time. 22 See, e.g., Abbott Lab. v. Gardner, 387 U.S. 136, 139-41 (1967). The right of action 23 28 U.S.C. § 2401(a). does not differ from plaintiff to plaintiff. It accrues for all plaintiffs as soon as any plaintiff can sue.

Second, consider the public nature of the right to administrative procedure. Administrative procedure provides the public with the right to participate in agency decisionmaking and requires agencies to deliberate about their decisions. It provides public participation rights. 24 See Kristin E. Hickman & Richard J. Pierce, Jr., Administrative Law Treatise § 5.3 (7th ed. 2018) (explaining that administrative procedure “provide[s] interested members of the public an opportunity to comment in a meaningful way on the agency’s proposal”); see also Kenneth Culp Davis, Administrative Law and Government 121 (2d ed. 1975) (“The system prescribed by § 553 of APA . . . is probably one of the greatest inventions of modern government. The system is informal and efficient, and yet it gives affected parties a chance to influence the content of rules.”). Because of these public rights, when an agency fails to follow administrative procedure, the resulting injury is “incurred by all persons” at that time. 25 Shiny Rock Mining Corp. v. U.S., 906 F.2d 1362, 1365 (9th Cir. 1990). It is a “denial of process to the public at large.” 26 Herr v. U.S. Forest Service, 803 F.3d 809, 820 (6th Cir. 2015). Such an administrative procedure claim is limited by the earlier-accruing six-year limitations period. 27 The rule is different for some claims that result from the application of a regulation to a plaintiff. In this case, later accrual applies if the plaintiff’s claim is that the regulation exceeds the authority of a substantive authorizing statute. See Wind River Mining Corp. v. U.S., 946 F.2d 710, 714 (9th Cir. 1991).

The rights to public participation provided by administrative procedure are secured in several ways. The check of private litigation works alongside legislative 28 See Josh Chavetz, Congress’s Constitution 61-73 (2017) (discussing Congressional control and oversight of agencies through budgetary and appropriations mechanisms). and executive 29 See, e.g., Elena Kagan, Presidential Administration, 114 Harv. L. Rev. 2245, 2253-54 (discussing presidential control and oversight). oversight mechanisms to keep administrative agencies in line. As with election 30 Statutes constrain voters’ ability to object to election illegalities. See, e.g., Tex. Elec. Code Ann. § 212.022 (2023) (allowing candidate petition); id. § 212.024(b)(2) (allowing twenty-five voters to petition); id. § 212.028(a) (imposing a deadline of 5 PM on the second day after the election). and legislative 31 For example, there is no practical ability to challenge a revenue act of Congress on the grounds that the House did not originate it if legislative records endorse the statute. See Field v. Clark, 143 U.S. 649, 672-73 (1892) (providing legislative journals as evidence of a statute’s validity because of “coequal and independent departments”); see also Tara Leigh Grove, The Lost History of the Political Question Doctrine, 90 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 1908, 1934–35 n.141 (2015) (explaining that courts apply an evidentiary rule in Origination Clause cases rather than treating them as raising a nonjusticiable political question). procedure, the private right to sue to vindicate the public right to legal process is limited in administrative procedure, in part because other oversight mechanisms are also available.

Finally, consider reliance. Limitations periods are a classic way in which the law provides stability, 32 See, e.g., David Crump, Statutes of Limitations: The Underlying Policies, 54 U. Louisville L. R. 437, 442 (2016) (citing “peace” as one reason for limitations). and in an administrative procedure case like AHM, this stability protects diverse reliance interests. The reliance interest of patients and providers, particularly with respect to the approval of mifepristone in 2000 and expansion of access in 2016, is clear from the Abortion Pills narrative. 33 See Cohen et al., supra note 1, at 390-91 (explaining the challenges faced by antiabortion advocates because of the “collateral damage” of abortion bans). The reliance interest of the pharmaceutical industry is also at stake. 34 Brief for the Pharm. Rsch. and Mfrs. of Am. as Amicus Curiae in Support of Petitioners at 19-21, U.S. FDA. v. All. for Hippocratic Med., Nos. 23-235, Danco Lab’y LLC v. All. for Hippocratic Med., Nos. 23-236 (U.S. Oct. 12, 2023). In AHM, invalidating the FDA’s actions would disrupt not only the medication abortion status quo, but also the FDA’s regulatory framework and established business and investment decisions across that industry as a whole. 35 Brief of Food and Drug Law Scholars as Amici Curiae in Support of Defendants’ Opposition to Plaintiffs’ Motion for Preliminary Injunction, at 26-27, All. for Hippocratic Med. v. U.S. FDA., No. 2:22-CV-00233-Z, (N.D. Tex. Apr. 7, 2023).

III. AHM Time Bar Analysis

A. Timeline

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration sits at the center of the fight over mifepristone. It approved the medicine more than two decades ago. 36 U.S. FDA, Approval Letter for Mifepristone (Sept. 28, 2000), https://perma.cc/3LFB-GMDU.

Leaving aside the generic approval, 37 See Petition for Writ of Certiorari at 10, U.S. FDA. v. All. for Hippocratic Med., No. 23-236 (Sept. 8, 2023) (indicating that the generic approval is not at issue). there are five FDA actions challenged in the AHM case.

First, in the “2000 Approval,” the FDA approved mifepristone. 38 Complaint at 2-3, All. for Hippocratic Med. v. U.S. FDA., No. 22-CV-233, (N.D. Tex. Apr. 7, 2023).

Second, in the “March 2016 Petition Denial,” the FDA denied a citizen petition filed in 2002 by the American Association of Pro-Life Obstetricians and Gynecologists (AAPLOG) and others, which challenged the 2000 Approval. 39 See id. at 3-4.

Third, in the “March 2016 Amendments,” the FDA modified Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS) rules for the prescription and distribution of mifepristone. These changes allowed at-home administration, increased the maximum gestational age, and allowed a broader set of providers to prescribe mifepristone. 40 See id. at 4.

Fourth, in the “2021 Petition Denial,” the FDA denied a citizen petition filed in 2019 by AAPLOG and others, which challenged the March 2016 Amendments. 41 See id. at 5.

Fifth, in the “2021 Non-Enforcement Decision,” the FDA stated that it would not pursue enforcement action relating to prescription by mail “during the COVID-19 public health emergency.” 42 See id. at 5.

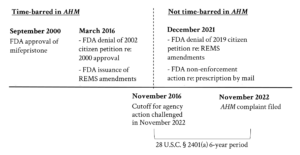

The window of time for final agency actions that can be challenged in AHM is six years back from November 18, 2022, when the AHM complaint was filed. 43 See id. at 1. This means that only FDA actions taken after November 18, 2016 may be challenged. Challenges to the 2000 Approval, the March 2016 Petition Denial, and the March 2016 Amendments were filed too late. Challenges to the 2021 Petition Denial and to the 2021 Non-Enforcement Decision are timely. Figure 1, below, summarizes.

Figure 1: Application of Six-Year Time Bar in AHM

The Fifth Circuit correctly time-barred challenges to the 2000 Approval and the March 2016 Petition Denial. 44 All. for Hippocratic Med. v. U.S. FDA., 78 F.4th 210, 242 (5th Cir. 2023) (holding the 2000 Approval and 2016 Petition Denial likely time-barred). But it incorrectly considered challenges to the March 2016 Amendments. Instead of analyzing whether the March 2016 Amendments were still open to administrative procedure challenge, the AHM majority assumed the issue away. 45 See id. at 245 (assuming parties’ agreement that challenge to March 2016 Amendments was timely). The only explanation given was that the parties agreed that the challenge to the March 2016 Amendments was timely. But the record does not reflect any waiver of the time bar by defendants. 46 Neither the briefs nor the hearing transcripts mention any waiver. Instead, they properly raised it in their response to the plaintiffs’ complaint. 47 See Fed. R. Civ. P. 8(c) (requiring affirmative defense in answer); Defendants’ Opposition to Plaintiffs’ Motion for a Preliminary Injunction at 16, All. for Hippocratic Med. v. U.S. FDA., No. 2:22-CV-00223-Z, 2023 WL 2825971 (N.D. Tex. Apr. 7, 2023) (“[A]ll of plaintiffs’ claims are untimely or unexhausted.”).

This is enough to preserve the defense. 48 A court may decide that an affirmative defense, such as a limitations period, is preserved with a plaintiff has enough notice of the defense and is not unfairly surprised by it, even when technical errors are made in pleading. See e.g., Smith v. Travelers Cas. Ins. Co., 932 F.3d 302, 308-10 (5th Cir. 2019) (holding timely a limitations period defense raised two years after the defendant’s initial answer to the plaintiff’s complaint); see also Tahoe-Sierra Pres. Couns., Inc. v. Tahoe Reg’l Plan. Agency, 216 F.3d 764, 788 (9th Cir. 2000) (explaining that if the defendant’s allegation of an affirmative defense is vague or defective, it can still be preserved so long as there is no prejudice or unfair surprise for the plaintiff), overruled on other grounds, Gonzalez v. Arizona, 677 F.3d 383 (9th Cir. 2012).

B. Administrative Petitions Do Not Extend Limitations Periods

Without much analysis, the district court decision in AHM assumed that the 2019 citizen petition automatically extended the time for challenging the March 2016 Amendments. 49 All. for Hippocratic Med. v. U.S. FDA, No. 22-CV-233, 2023 WL 2825871, at *9 (N.D. Tex. Apr. 7, 2023) (assuming that a citizen petition automatically extends the time to litigate the underlying regulation). This was a mistake. Administrative petitions generally do not extend the time to challenge an underlying regulation. Instead, they produce a separate final agency action – such as the 2021 Petition Denial—that is subject to separate judicial review. 50 See, e.g., McAfee v. U.S. FDA., 36 F.4th 272, 274-75 (D.C. Cir. 2022) (reviewing a citizen petition denial).

The Fifth Circuit did not correct this district court mistake. The Supreme Court should. The Justices, including those dissenting, should not assume that a challenge to the March 2016 Amendments is timely in AHM. This would incorrectly suggest that plaintiffs can leverage citizen petitions into an infinite ability to challenge stale administrative procedure foot faults. Ignoring the application of the time bar to the March 2016 Amendments would suggest that a later citizen petition automatically reopens the challenged regulatory action, instead of confining review to whether the agency properly considered and decided the citizen petition itself. It also would step on the Supreme Court’s separate effort this Term to develop the law on time of accrual for 28 U.S.C. § 2401(a) in Corner Post. 51 Corner Post, Inc. v. Bd. of Governors of Fed. Res. Sys., No. 22-1008, 2023 WL 6319653 (U.S. Sept. 29, 2023).

The 2021 Petition Denial is itself a “final agency action” which can be reviewed. But the review should apply an arbitrary or capricious review standard to the 2021 Petition Denial—not to the March 2016 Amendments. 52 See, e.g., McAfee, 36 F.4th at 274, 277-78 (noting extremely deferential standard of review for agency petition denial and refusing to require a raw butter exemption from FDA regulations about pasteurization); Tummino v. Hamburg, 936 F. Supp. 2d 162, 166 (E.D.N.Y 2013) (discussing a previous refusal to grant the plaintiff the relief sought because of the FDA’s expertise). The review must refer to the citizen petition record—not the administrative record for the original rulemaking. 53 See, e.g., Graceway Pharm., Inc. v. Sebelius, 783 F. Supp. 2d 104, 114-115 (D.D.C. 2011) (confining review of citizen petition to its record and upholding FDA disposition). Finally, the typical remedy is to remand the citizen petition to the agency for reconsideration—not to invalidate the original rule. 54 See, e.g., Tummino v. Torti, 603 F. Supp. 2d 519, 522-24 (E.D.N.Y. 2009) (remanding citizen petition denial after finding undue political influence).

Allowing plaintiffs to directly challenge the March 2016 Amendments because of the intervening 2019 citizen petition directly contradicts available decisions of at least two Courts of Appeals. The Fourth Circuit time-barred a challenge to a 1989 Federal Highway Administration highway location decision filed by a plaintiff neighborhood association in 1997, despite an administrative complaint filed by the association in 1994. 55 See Jersey Heights Neighborhood Ass’n v. Glendening, 174 F.3d 180, 185-186 (4th Cir. 1999) (time-barring claim). Similarly, the First Circuit time-barred a challenge to a 1985 Department of Housing and Urban Development fair market rent assessment decision filed by a housing rehabilitation project in June 1995, even though the housing project pursued administrative remedies until April 1995. 56 See Trafalgar Capital Assocs., Inc v. Cuomo, 159 F.3d 21, 34-37 (1st Cir. 1998) (holding that claim accrued before the completion of permissive administrative remedies).

If neighbors cannot use an administrative petition to extend their time to challenge an earlier highway location decision, and a housing rehabilitation project cannot use administrative remedies to extend its time to challenge an earlier rent assessment, then doctors cannot use a citizen petition to extend their time to challenge the FDA’s March 2016 Amendments that changed the REMS prescription and distribution rules for mifepristone. And this issue extends over all of federal administrative law, because the APA allows general petitions for agency action. 57 See 5 U.S.C. § 553(e) (“Each agency shall give an interested person the right to petition for the issuance, amendment, or repeal of a rule.”). It would be astonishing if Section 553(e) of the APA had the capacity to reopen challenges to stale administrative procedure mistakes. If petitions are discovered to have this ability, a huge volume of decades-old administrative decisions would be newly opened to challenge on administrative procedure grounds such as inadequate notice and comment.

C. Constructive Reopening and Equitable Tolling

Even if a citizen petition does not automatically restart the six-year time bar under 28 U.S.C. § 2401(a), plaintiffs can argue for an extension of the limitations period under two headings. One is reopening. The other is equitable tolling. But as the Fifth Circuit correctly held, these do not save the challenges to the 2000 Approval or the March 2016 Petition Denial. 58 See All. for Hippocratic Med. v. U.S. FDA, 78 F.4th 210, 242 (5th Cir. 2023) (holding the 2000 Approval and 2016 Petition Denial likely time-barred). They do not save the challenges to the March 2016 Amendments either.

The most straightforward version of reopening is when the agency itself reopens an issue. 59 Sierra Club v. EPA, 551 F.3d 1019, 1024 (D.C. Cir. 2008). Agencies reopen an issue by “holding out the unchanged section as a proposed regulation, offering an explanation for its language, soliciting comments on its substance, and responding to the comments in promulgating the regulation in is final form.” 60 Id. (citing and quoting Am. Iron & Steel Inst. v. EPA, 886 F.2d 390, 397 (D.C. Cir. 1989)). This straightforward concept of reopening does not apply in AHM, because the FDA did not itself initiate any reconsideration of its mifepristone rules. Rather, AHM involves “constructive reopening”—a doctrine developed by the D.C. Circuit, which the Supreme Court has not embraced. 61 Kennecott Utah Copper Corp. v. U.S. Dep’t of Interior, 88 F.3d 1191, 1214-1215 (D.C. Cir. 1996) (explaining constructive reopening). “Constructive reopening” applies when an agency “‘significantly alters the stakes of judicial review’ as the result of a change that ‘could have not been reasonably anticipated.’” 62 Sierra Club v. EPA, 551 F.3d 1019, 1025 (D.C. Cir. 2008) (citing and quoting Kennecott Utah Copper Corp., 88 F.3d at 1226-1227 and Env’t. Def. v. EPA, 467 F.3d 1329, 1334 (D.C. Cir 2006)). The magnitude of alteration needed to invoke constructive reopening has been described as a “sea change.” 63 Nat’l Biodiesel Bd. v. EPA, 843 F.3d 1010, 1017 (D.C. Cir. 2016) (quoting Nat’l Res. Def. Council v. EPA, 571 F.3d 1245, 1266 (D.C. Cir. 2009) (per curiam)).

The AHM plaintiffs argued that the March 2016 Amendments constructively reopened the 2000 Approval. But as the Fifth Circuit explained, “the opposite is true. The FDA took the restrictions imposed in 2000 as a given” when it issued the March 2016 Amendments. 64 All. for Hippocratic Med. v. U.S. FDA, 78 F.4th 210, 243 (5th Cir. 2023). There was no significant alteration, let alone one that was not “reasonably anticipated.” 65 Id. at 243-44. AHM is like Natural Resources Defense Council, in which the EPA changed the details of how to calculate the value of offset credits. 66 Nat’l Res. Def. Council v. EPA, 571 F.3d 1245, 1263-1266 (D.C. Cir. 2009) (allowing pre-application source emission reduction to count for offset credits). This made it easier to meet emissions requirements, within the context of a continuing “basic regulatory scheme.” 67 Id. at 1266 (holding no constructive reopening).

Despite Judge Ho’s dissent on this point at the Fifth Circuit, 68 All. for Hippocratic Med. v. U.S. FDA, 78 F.4th at 260-263 (Ho, J. concurring in part and dissenting in part). AHM is not like Sierra Club, in which a rule change removed the requirement that a factory must show that it was doing its “reasonable best” to stay under emission limits in order to obtain a permit to pollute. 69 Sierra Club, 551 F.3d at 1022-1023 (D.C. Cir. 2008). Removing the “reasonable best” requirement changed a basic prerequisite for a company to receive approval to pollute. In contrast, when the FDA modified prescription and administration terms in its March 2016 Amendments, it did not change any prerequisite for the manufacture and distribution of mifepristone. Moreover, there is nothing in the record—or in Judge Ho’s opinion, which did not consider the point—to suggest that the March 2016 Amendments were unexpected. Instead, there is every indication that the March 2016 Amendments were “reasonably anticipated,” 70 All. for Hippocratic Med. v. U.S. FDA 78 F.4th at 243 (quoting Env’t Def. v. EPA, 467 F.3d 1329, 1334 (D.C. Cir. 2006)). as a logical outgrowth of the FDA’s conclusion that “mifepristone is safe and effective.” 71 Id. (holding the FDA did not constructively reopen the 2000 approval).

The argument that the 2021 Petition Denial constructively reopened the March 2016 Amendments makes even less sense. The 2021 Petition Denial confirmed the March 2016 Amendments in almost every detail. They did not produce a material change, let alone a “sea change,” let alone an unexpected sea change, to the FDA’s mifepristone rules.

Plaintiffs might argue that the filing of the 2019 citizen petition, and the fact that the FDA considered the petition for about two years, equitably tolled their ability to challenge the March 2016 Amendments. 72 See United States v. Kwai Fun Wong, 575 U.S. 402, 410-11 (2015) (holding that standard statute of limitations language does not bar equitable tolling even when the text indicates the limitations period is mandatory); Jackson v. Modly, 949 F.3d 763, 776-78 (D.C. Cir. 2020) (holding 28 U.S.C. § 2401(a) not jurisdictional). But extended consideration of a petition is not an agency error that would support equitable tolling. 73 Compare Irwin v. Dep’t of Veteran Aff., 498 U.S. 89, 95-96 (1990) (denying equitable tolling where plaintiff did not receive a relevant notice), with Socop-Gonzalez v. INS, 272 F.3d 1176, 1184-87, 1193-97 (9th Cir. 2000) (granting equitable tolling after INS officer gave incorrect advice to deportee). And the citizen petition did not prevent the plaintiffs from filing a lawsuit challenging the March 2016 Amendments. Even if the citizen petition had to be resolved before a complaint was filed, 74 See, e.g., Young v. United States, 535 U.S. 43, 50-51 (2002) (equitably tolling tax collection period while bankruptcy petition precluded collection). it was resolved by operation of law 150 days after filing. After 150 days, the statute deems that FDA has denied the petition through a “final agency action,” thus removing any obstacle to the plaintiffs’ ability to pursue the lawsuit. 75 See 21 U.S.C. § 505(q)(2)(A) (2012). This would extend the deadline to challenge the March 2016 Amendments from March 2022 to June 2022. The November 2022 challenge to the March 2016 Amendments would still be untimely.

Conclusion

Abortion pills are here to stay. One reason is the six-year limitations period of 28 U.S.C. § 2401(a), which provides a default time bar for administrative procedure challenges to federal rulemaking. The Supreme Court will consider this time bar when it reviews the Fifth Circuit’s AHM decision this Term. When it does, it should conclude that the challenges to the FDA’s 2000 Approval of mifepristone and to the FDA’s March 2016 Amendments are time-barred, although the challenge to the FDA’s 2021 Non-Enforcement Order regarding prescription by mail is timely. A careful analysis of the time bar in AHM will serve the development of the law on 28 U.S.C. § 2401(a)—which is also before the Court this Term in a different case, Corner Post. Limitations periods are traditionally conservative tools in that they block legal action that could produce change. But in AHM, this six-year time bar protects established progressive law—the legal status quo of reproductive rights described in Abortion Pills.

* Susan C. Morse is the Angus G. Wynne, Sr. Professor of Civil Jurisprudence and Associate Dean for Academic Affairs at the University of Texas School of Law. Leah R. Butterfield is a member of the University of Texas School of Law J.D. class of 2024. Many thanks to David Cohen, Mechele Dickerson, Tara Leigh Grove, Rachel Rebouché, Elizabeth Sepper, and Stephen Vladeck for helpful conversation and comments. This project has benefited from presentation at the University of Texas School of Law.