Essay

A Congressional Incapacity Amendment to the United States Constitution

John J. Martin *

Introduction

The U.S. Constitution provides little proper recourse for the incapacitation of a member of Congress. This is a problem. As of today, if a Senator were to suffer from, say, a stroke, said Senator’s constituents would lose half their representation in the Senate for upwards of months or even years, depending on the level of recovery needed. 1 See, e.g., Ali Zaslav & Morgan Rimmer, New Mexico Democratic Senator Back to Work About a Month After Suffering Stroke, CNN (Mar. 3, 2022, 12:13 PM EST), https://perma.cc/RU7D-ANKN. And if said Senator were to experience a more long-term illness, 2 See, e.g., John Bresnahan & Anna Palmer, Frail and Disoriented, Cochran Says He’s Not Retiring, POLITICO (Oct. 18, 2017, 4:53 PM EDT), https://perma.cc/ZE5Y-QTGL. that lack of effective representation could endure until the end of the Senator’s term. Replace the Senator with a Representative in this scenario and an entire congressional district is left voiceless in the House. These are not mere hypotheticals, of course. Each year, we read stories of congresspeople’s health issues preventing them from fully fulfilling their legislative duties. 3 See infra notes 20-22 and accompanying text. Recent controversies surrounding the health of Senators Dianne Feinstein and Mitch McConnell, for instance, have brought new national attention to the topic. 4 See Annie Karni, Feinstein, Back in the Senate, Relies Heavily on Staff to Function, N.Y. Times (May 28, 2023), https://perma.cc/E6V6-SXU9; Mitch McConnell Abruptly Stops Mid-Sentence During Press Conference, Guardian (July 26, 2023, 8:41 PM EDT), https://perma.cc/TW4Q-8H5U. Yet, there presently exist no practical means of ensuring that representation continues undisrupted for affected constituents. 5 See infra Part I.C. This is antithetical to our democracy. 6 See infra Part I.B. And with Congress’s average age on the rise, 7 See infra Figure 1. the problem may only get worse.

The United States has faced comparable difficulties in the past: When Dwight D. Eisenhower experienced serious illness during his presidency, concerns arose over how to handle a crisis of presidential incapacity. 8 See Lawrence J. Trautman, The Twenty-Fifth Amendment: Incapacity and Ability to Discharge the Powers and Duties of Office?, 67 Clev. St. L. Rev. 373, 384-85 (2019). When these concerns reached their peak following the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, Congress immediately acted and passed the Twenty-Fifth Amendment to the Constitution in 1965, which the states ratified soon thereafter. 9 Id. at 385. The Twenty-Fifth Amendment, among other things, provides mechanisms for both a voluntary interim transfer of presidential powers to the Vice President and an involuntary transfer of such powers whenever the President is deemed unable to discharge the duties of their office. 10 U.S. Const. amend XXV, §§ 3-4. While voluntary transfer rarely occurs, and involuntary transfer has never occurred, the Twenty-Fifth Amendment has been integral to filling gaps within our constitutional democratic framework. 11 See Brian C. Kalt, Section Four of the Twenty-Fifth Amendment: Easy Cases and Tough Calls, 10 ConLawNOW 153, 159 (2019) (“Section 4 has never been used before . . . .”); infra note 56 (noting the four times voluntary transfer was used). The Twenty-Fifth Amendment has also been crucial to ensuring that the executive branch remains functioning if the President cannot fulfill their duties, an admittedly lesser concern in the context of incapacitation of individual members of Congress. This Essay recognizes and touches upon this distinction briefly. See infra notes 46-47 and accompanying text. Over fifty years later, this Essay now argues for the implementation of a similar amendment that tackles the problem of congressional incapacity.

There has been little discussion within legal scholarship about the incapacitation of congresspeople, despite its democratic implications. The few existing pieces that have discussed the topic have largely adopted an institutional perspective, focusing on the issue of mass, Congress-wide incapacitation caused by terrorism or pandemic, rather than a constituency-minded perspective that concentrates on individual instances of incapacitation. 12 See, e.g., Continuity of Gov’t Comm’n, Am. Enter. Inst., The Continuity of Congress 1 (2022), https://perma.cc/7F75-MUTN; Howard M. Wasserman, Continuity of Congress: A Play in Three Stages, 53 Cath. U. L. Rev. 949, 949 (2004); James C. Ho, Ensuring the Continuity of Government in Times of Crisis: An Analysis of the Ongoing Debate in Congress, 53 Cath. U. L. Rev. 1049, 1049 (2004). This Essay distinguishes itself from existing literature by focusing on the latter. Using the Twenty-Fifth Amendment as a blueprint, this Essay provides one of the first attempts to lay out how precisely one could resolve the incapacity of individual Congress members—simply referred to as “congressional incapacity” for the remainder of the Essay—by constitutional amendment.

Specifically, the Essay imagines such an amendment having two sections. The first section would permit members of Congress to temporarily transfer the duties of their office to an interim appointee in times of short-term incapacity, with limitations regarding the residency and party affiliation of said appointee. 13 See infra Part III.A. The second section would create a process for involuntary transfers of such duties whenever a member of Congress has a long-term incapacitation but is unable or unwilling to use the voluntary transfer process or resign. 14 See infra Part III.B. This process would be multi-layered, involving the will of the affected constituents (either by direct vote or proxy via state legislatures), an independent board of medical experts appointed and regulated by Congress, and potentially Congress itself. Through this design, the process would ensure that decisions of involuntary transfer would still maintain democratic legitimacy all while minimizing the effects of personal or partisan biases.

I do not claim to have the perfect solution to congressional incapacity. In fact, I invite and hope for responses that critique and build upon my own proposal. The primary purpose of this Essay is simply to spark a conversation on an uncomfortable, but vital, national issue. This Essay proceeds as follows: Part I discusses the congressional incapacity problem, including its prevalence, antidemocratic effects, and lack of current solutions. Part II then overviews the Twenty-Fifth Amendment’s history, text, and shortcomings. Finally, Part III outlines a potential congressional incapacity amendment, addressing likely concerns and criticisms along the way.

I. The Congressional Incapacity Problem

The topic of congressional incapacity—i.e., the temporary or permanent mental or physical inability of a member of Congress to perform their duties—has recently become a subject of great attention. 15 See, e.g., Jerry Goldfeder, If Dianne Feinstein Were President, Just Sec. (Apr. 19, 2023), https://perma.cc/L3CQ-N2XA; Norm Ornstein, Dianne Feinstein Reminded Us That the Senate Doesn’t Have a Plan, Atlantic (Apr. 19, 2023), https://perma.cc/A4GH-WAHH; What If a Member of Congress Is Severely Incapacitated and Cannot Perform the Duties of the Job?, Bipartisan Pol’y Ctr. (Mar. 26, 2020), https://perma.cc/JBS4-LC26. Disability was, in fact, hardly a thought at the time of the Constitution’s drafting, 16 See S. Rep. No. 89-66, at 4-5 (1965) (noting the only reference to disability at the Constitutional Convention as coming from John Dickinson); Trautman, supra note 8, at 377. and since then there has been little movement to address the issue as it pertains to members of Congress. Nevertheless, due to a variety of factors—namely an aging Congress, 17 See infra Figure 1. growing media coverage, 18 See, e.g., sources cited supra note 15; cf. Marc Gallofré Ocaña, Lars Nyre, Andreas L. Opdahl, Bjørnar Tessem, Christoph Trattner & Csaba Veres, Towards a Big Data Platform for News Angles, 2316 CEUR Workshop Procs. 17, 21 (2019) (“[M]any newsrooms . . . [are] producing more news than ever.”). and recent health concerns sparked by COVID-19 19 See Ian Millhiser, How to Make Sure Congress Can Still Function if Its Members Are Quarantined, Vox (Mar. 24, 2020, 8:30 AM EDT), https://perma.cc/ZW2B-GDXF. —the question of procedures surrounding the incapacitation of members of Congress has garnered increasing consideration. As this Part explains, though, despite its growing prevalence and antidemocratic effects, congressional incapacity remains an unsolved problem.

A. Prevalence

It has become common, if not expected, that at least one Senator or Representative will take a considerable leave of absence in any given year for health-related reasons. In recent congressional sessions, various members have spent weeks or months in recovery from medical conditions, including brain hemorrhages, strokes, physical trauma, and depression. 20 See Goldfeder, supra note 15. While such leaves are justifiable, members who take them are often left temporarily unable to perform their congressional duties. Furthermore, beyond temporary leaves of absence, there have been reports of multiple members suffering from more long-term afflictions that jeopardize their ability to continue serving in Congress altogether. Senators Thad Cochran and Strom Thurmond, for instance, both faced growing concerns toward the end of their lives regarding their capacity to remain active Senators in the midst of age-related health complications. 21 See Thad Cochran’s Illness Shows Risks to Republicans of Aging Senate, CBS News (Oct. 17, 2017, 6:56 AM), https://perma.cc/JVH9-EM7M; David Firestone & Philip Shenon, A Hushed but Vital Issue: Thurmond’s Health, N.Y. Times (Mar. 9, 2001), https://perma.cc/X83X-G2UP. More recently, numerous politicians and groups have called upon Senator Feinstein to resign in light of her reportedly declining health. 22 Alexander Bolton, More than 60 California Liberal Groups Call on Feinstein to Resign, The Hill (Apr. 21, 2023, 1:29 PM ET), https://perma.cc/XVJ9-77LR; Nicholas Wu, Ro Khanna Said He’s Giving Dianne Feinstein “the Benefit of the Doubt” but Still Thinks She Should Resign as She Returns to the Senate, POLITICO (May 11, 2023, 4:25 PM EDT), https://perma.cc/4DYA-JDKX. Likewise, Senator McConnell has faced pressure to step down as Senate minority leader following an episode in which he froze mid-press conference and subsequent reports about a recent hospitalization. 23 See James Bickerton, Mitch McConnell Is Facing More Pressure to Resign, Newsweek (Aug. 12, 2023, 12:31 PM EDT), https://perma.cc/H9DP-W887.

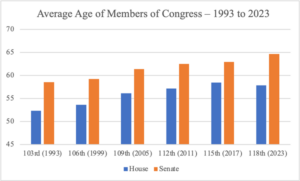

Perhaps this seemingly growing prevalence of congressional incapacity can be blamed in part on growing media scrutiny—long gone are the days in which elected officials could keep their debilitating conditions effectively hidden from the public (and thankfully so). 24 For example, President Woodrow Wilson managed to largely keep secret the effects of a severe stroke that left him entirely incapacitated throughout his final two years in office. See Kenneth R. Crispell & Carlos F. Gomez, Hidden Illness in the White House 69-74 (1988). Nevertheless, it is difficult to ignore the role that age likely plays here. As Figure 1 below shows, the average age of Congress has notably increased over the past three decades. In 1993, the average Representative and Senator were 52.3 and 58.5 years old, respectively. 25 Data retrieved from Average Age, Generations of Am. Leaders, https://perma.cc/PYM4-63HU(archived July 27, 2023). Today, those numbers have risen to 57.8 and 64.4 years old, representing the fourth-oldest House and oldest Senate in history. 26 Id. These numbers become more astonishing when broken down by committee: As Figure 2 highlights, some of the most powerful House and Senate committees boast even higher average ages this session. Suffice to say, our federal legislature is an elderly body.

Figure 1 27 Id.

Figure 2—Average Age of Powerful Committees of 118th Congress 28 Average committee age data is original data retrieved by the author. Ages reflect the age of members of Congress upon the start of the 118th Congress on January 3, 2023. Open Secrets identifies “Energy & Commerce, Appropriations[,] and Ways & Means” as among the “most powerful” House committees. See Top Congressional Committees, Open Secrets, https://perma.cc/NAY9-X3Z6 (archived July 27, 2023). Equivalent Senate committees are included in the table, though the Senate has no Energy & Commerce committee.

| Congressional Chamber | Committee | Average Age | Difference from Average Age of Relevant Chamber |

|---|---|---|---|

| Senate | Appropriations | 65.7 | +1.3 years |

| Senate | Finance | 66.6 | +2.2 years |

| House | Appropriations | 60.3 | +2.5 years |

| House | Energy & Commerce | 61.3 | +3.5 years |

| House | Ways & Means | 60.3 | +2.5 years |

Being old does not, of course, necessarily make one unqualified for public office. It is no secret, however, that with age comes more health issues. 29 See Ageing and Health, World Health Org. (Oct. 1, 2022), https://perma.cc/FBP9-8X7T. And with long-term trajectories for life expectancy generally looking positive, 30 See James W. Vaupel, Francisco Villavicencio & Marie-Pier Bergeron-Boucher, Demographic Perspectives on the Rise of Longevity, 118 PNAS e2019536118, at 1, 4 (2021) (“[M]ost children born in the last two decades in countries with high life expectancy will, if past progress continues, celebrate their 100th birthday.”). But see Life Expectancy in the U.S. Dropped for the Second Year in a Row in 2021, Ctrs. for Disease Control & Prevention (Aug. 31, 2022), https://perma.cc/BR55-K8MU. Congress may very likely continue to skew older. If so, we should expect age-related incapacitation of members of Congress to remain, if not rise. And such instances would only add to the myriad other causes of incapacitation that occur independent of age. 31 See, e.g., Cindy Saine, US Representative Giffords Resigns Year After Arizona Shooting, VOA (Jan. 24, 2012, 7:00 PM), https://perma.cc/5JUF-ZAWW; Biden Resting After Surgery for Second Brain Aneurysm, N.Y. Times (May 4, 1988), https://perma.cc/78TT-JPQ5. As the next Subpart discusses, this poses issues for our democratic system.

B. Antidemocratic Effects

Congressional incapacity can lead to a variety of antidemocratic consequences. On a theoretical level, it often leaves millions of Americans without federal representation for months at a time, if not indefinitely. Representation has always been a vital part of American democracy. 32 See Aziz Z. Huq, The Counterdemocratic Difficulty, 117 Nw. U. L. Rev. 1099, 1134 (2023); see also Nadia Urbinati, Representative Democracy: Principles & Genealogy 18-20 (2006) (“[D]emocratization and the representative process share a genealogy.”). From youth, we are ingrained with the Founding-era maxim of “no taxation without representation.” Our Constitution guarantees representation of state citizens in both federal government 33 See U.S. Const. art. I, § 2, cl. 1; id. amend. XIV, §§ 1-2; id. amends. XV, XVII, XIX, XXIV, XXVI. and state government 34 See id. art. IV, § 4 (“The United States shall guarantee to every State in this Union a Republican Form of Government . . . .”). But see Rucho v. Common Cause, 139 S. Ct. 2484, 2506 (2019) (“[T]he Guarantee Clause does not provide the basis for a justiciable claim.”). At the very least, state legislative districts are constitutionally required to be apportioned equally by population. See Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533, 568-69 (1964). Thus, congressional incapacity, if left unaddressed, undermines a fundamental constitutional democratic principle: When a Representative takes months’ leave for medical reasons, their district is effectively rendered voiceless in the House for that period of time. And when a Senator’s declining health prevents them from fulfilling their duties, their state loses half its representation in the Senate until said Senator resigns, loses reelection, or dies.

More practically speaking, one incapacitated member of Congress has the potential to entirely gridlock the legislative process. Take, for instance, congressional committees, which often gatekeep which bills make it to the House and Senate floors. 35 As Woodrow Wilson once aptly put it, “Congress in session is Congress on public exhibition, whilst Congress in its committee rooms is Congress at work.” Woodrow Wilson, Congressional Government 79 (15th prtg. 1901). These committees typically operate on thin partisan margins, meaning that if one member fails to participate in committee votes—particularly one from the political party in power—said committee may be unable to refer bills to a floor vote. 36 See, e.g., Burgess Everett & Katherine Tully-McManus, Republicans Line Up Against Replacing Feinstein on Critical Committee, POLITICO (Apr. 17, 2023, 7:03 PM EDT), https://perma.cc/CTN6-4UEU(explaining how Senator Feinstein’s absence from the Senate Judiciary Committee impeded the confirmation of President Joe Biden’s judicial nominees). This effect can be especially prominent in today’s exceptionally polarized Congress. 37 See Christopher Hare & Keith T. Poole, The Polarization of Contemporary American Politics, 46 Polity 411, 428 (2014) (“[T]he Democratic and Republican parties in Congress are more polarized than at any time since the end of Reconstruction . . . .”). One incapacitated member could thus impede large swaths of the legislative agenda of a democratically elected Congress or presidential administration.

While much more could be said on this subject, it is clear that, at the very least, congressional incapacity can have some deteriorating effect on our democratic system. Nevertheless, congressional incapacity continues to endure without any decent remedy.

C. Current (Lack of) Options

When it comes to existing means of handling congressional incapacity, each option seems less appealing than the last. The most obvious starting point is the Expulsion Clause, which reads as follows: “Each House may determine the Rules of its Proceedings, punish its Members for disorderly Behaviour, and, with the Concurrence of two thirds, expel a Member.” 38 U.S. Const. art I, § 5, cl. 2. On its face, then, the clause would appear to provide a clear-cut solution to congressional incapacity by ostensibly permitting the expulsion of extraordinarily incapacitated members.

This is, however, not so. For one—and perhaps fortunately—the clause’s broad language has not translated into broad practice. Out of the twenty members that have been expelled in U.S. history, eighteen were for disloyalty to the nation and two were for corruption. 39 Todd Garvey, Cong. Rsch. Serv., R45078, Expulsion of Members of Congress: Legal Authority and Historical Practice 10-11 (2018), https://perma.cc/KN2S-EBMU (noting that 85% of expulsions occurred during the Civil War). Accordingly, while Congress can technically expel members for any reason, the body has appeared to cabin its usage to circumstances involving severe criminal conduct. The Expulsion Clause’s rare application also speaks to its impeditive nature. For instance, by leaving the decision of expulsion in the hands of the very colleagues of those threatened with it, votes are likely to be based on personal or political feelings rather than more objective considerations. The recent failed attempt to expel George Santos from the House showcases these inevitable dynamics. 40 See Caitlin Yilek, House Republicans Block Democratic Effort to Expel George Santos from Congress, CBS News (May 17, 2023, 7:49 PM), https://perma.cc/5WR2-U765.

Furthermore, even if used, the clause’s process for expulsion—a two-thirds vote from a given chamber—would only exacerbate, rather than fix, the antidemocratic effects of congressional incapacity. Rather than including affected constituents in the process, 41 For suggested processes that would incorporate affected constituencies, see infra Part III.B.1. the decision would be left entirely to other elected officials, nearly all of whom represent other constituencies with far less at stake in the matter.

Alternatives to the Expulsion Clause do not fare much better. Incapacitated members of Congress could voluntarily resign and be replaced either by a temporary appointee or through a special election (the latter option being the only choice for House members). 42 See U.S. Const. art. I, § 2, cl. 4; Vacancies in the United States Senate, Nat’l Conf. of State Legislatures, https://perma.cc/RGR4-2PSR (last updated Apr. 1, 2023). Elected officials are not, however, typically keen on giving up political power, even when they are nearly unable to vote on the floor. 43 See, e.g., Firestone & Shenon, supra note 21 (“Mr. Thurmond continues to make his way into the chamber for votes, but he walks haltingly and only with the help of aides, often one on each elbow.”). One could also be so incapacitated that they no longer possess the faculties to even render such a decision. And resignation also provides no answer for those members experiencing only temporary incapacitation.

Given the lack of a practical solution to congressional incapacity, the time is ripe to take action and construct a formal process to properly redress the issue. Exactly how to do so remains up for debate, though the answer likely requires a constitutional amendment. 44 See supra notes 76-77 and accompanying text. Fortunately, there already exists a framework tackling a similar issue to which we can look for guidance: the Twenty-Fifth Amendment to the Constitution.

II. The Twenty-Fifth Amendment as a Framework

Adopted over fifty years ago, the Twenty-Fifth Amendment is the only amendment to presently confront the issue of an incapacitated leader. 45 The Twentieth Amendment covers instances of incapacitated Presidents-elect, but not any sworn-in elected officials. See U.S. Const. amend. XX, § 3. As such, and having been recently subjected to heightened scrutiny during the Trump presidency, 46 See, e.g., Joel K. Goldstein, Talking Trump and the Twenty-Fifth Amendment: Correcting the Record on Section 4, 21 U. Pa. J. Const. L. 73, 74-75 (2018); Paul F. Campos, A Constitution for the Age of Demagogues: Using the Twenty-Fifth Amendment to Remove an Unfit President, 97 Denv. L. Rev. 85, 86-88 (2019); John Hudak, Invoke the 25th Amendment to Save the Country from Donald Trump, Brookings Inst. (Jan. 7, 2021), https://perma.cc/XUL4-22ZT. the Twenty-Fifth Amendment is an excellent resource for establishing the dos and don’ts of addressing the congressional incapacity problem. Presidential incapacity is not, of course, perfectly comparable to congressional incapacity. The former, for instance, effectively cripples the executive branch in its entirety, as the Constitution vests the “executive [p]ower” wholly in the President. 47 U.S. Const. art. II, § 1, cl. 1. Meanwhile, “legislative [p]owers” are vested in Congress as an institution, rendering the incapacitation of any individual member far less existentially consequential for our federal government. 48 Id. art. I, § 1. Still, this distinction does not undermine the undemocratic impact of congressional incapacity, nor does it mean that presidential incapacity and congressional incapacity cannot have like solutions. Accordingly, this Part briefly overviews the history and substance of the Twenty-Fifth Amendment, with a focus on sections three and four. It then identifies some strengths and weaknesses of section four, both in the process it lays out and the language it uses.

A. The Amendment

The Twenty-Fifth Amendment’s history could take up an entire book. 49 See generally, e.g., John D. Feerick, The Twenty-Fifth Amendment: Its Complete History and Applications (2d ed. 1992). I will not trouble the reader with such a detailed account. In brief, though, prior to 1967, the Constitution contained no clear textual guidance as to how the executive branch should proceed should the President be physically or mentally unable to fulfill their duties. 50 See Relating to the Problem of Presidential Inability: Hearing on S.J. Res. 28, S.J. Res. 35 and S.J. Res. 84 Before the Subcomm. on Const. Amends. of the S. Comm. on the Judiciary, 88th Cong. 10 (1963) (statement of Sen. Keating) (“Many citizens would be astonished to discover that the Constitution does not provide adequate procedures for the exercise of the President’s powers and duties in the event the President becomes temporarily disabled by illness.”). More shockingly, Article II did not even explicitly state that the Vice President becomes President upon the death of the current President. 51 See U.S. Const. art. II, § 1, cl. 6 (stating only that the powers and duties of the President “shall devolve on the Vice President” upon the death, resignation, or inability of the former); Campos, supra note 45, at 89-90. Following over 150 years of ambiguity—and numerous instances of presidential incapacitation—the assassination of John F. Kennedy eventually prompted Congress to pass the Twenty-Fifth Amendment to fill these constitutional gaps. 52 Trautman, supra note 8, at 83-85. The amendment’s ratification process was completed in 1967. 53 Id.

The amendment has four sections. The first two—which are not important for this Essay’s purpose—cover presidential and vice-presidential vacancies. 54 U.S. Const. amend XXV, §§ 1-2. Section three deals with the issue of temporary incapacitation. Specifically, the section states that:

Whenever the President transmits to the President pro tempore of the Senate and the Speaker of the House of Representatives his written declaration that he is unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office, and until he transmits to them a written declaration to the contrary, such powers and duties shall be discharged by the Vice President as Acting President. 55 Id. § 3.

Three Presidents have thus far used this option on four separate occasions. 56 See Goldstein, supra note 45, at 76, 76 n.6 (Ronald Reagan once and George W. Bush twice); Kate Sullivan, For 85 Minutes, Kamala Harris Became the First Woman with Presidential Power, CNN (Nov. 19, 2021, 12:29 PM EST), https://perma.cc/334P-R5GJ(Joe Biden once).

Finally, there is section four. Perhaps more heavily scrutinized than any other section, section four provides a process for involuntarily relieving the President of their powers and duties. While never used, the section is meant to ensure that the United States does not end up with a head of state too incapacitated to perform their role yet unwilling or unable to employ the section-three process. To begin the process, “the Vice President and a majority of either the principal officers of the executive departments or of such other body as Congress may by law provide” must deliver a written declaration to congressional leadership that “the President is unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office.” 57 U.S. Const. amend XXV, § 4. When this happens, the Vice President immediately becomes Acting President.

The President may, nevertheless, transmit their own written declaration to congressional leadership that they are, in fact, able enough to do so. Then, the Vice President and a majority of either the principal officers or “other body” have four days to again provide congressional leadership with another written declaration that “the President is unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office.” 58 Id. If the Vice President and principal officers/other body do not provide another written declaration by the end of that four-day window, the President resumes the powers and duties of their office. Should this occur, Congress must assemble within two days and decide the issue: If two-thirds of both chambers vote that the President is unable to discharge the powers and duties of the office, the Vice President remains Acting President. 59 Id. If not, the President reassumes the office.

Section four remains the sole constitutional provision providing a means of involuntarily transferring the powers of an incapacitated elected official. As such, by surveying its strengths and weaknesses, we can gain a better understanding of how to effectively address instances of congressional incapacity.

B. Strengths and Weaknesses of Section Four

One of section four’s greatest assets is that it requires multiple bodies to weigh in on the President’s capabilities—the Office of the Vice President, the principal officers (or some “other body”), and potentially both chambers of Congress. This bakes the principle of checks and balances into the section-four process, thus shielding it from being reduced to a purely political tool. 60 Joel K. Goldstein, Taking from the Twenty-Fifth Amendment: Lessons in Ensuring Presidential Continuity, 79 Fordham L. Rev. 959, 987-91 (2010). The order of the process further reinforces this effect: By placing the first move in the hands of the Vice President and principal officers, who typically share the same partisan affiliation as the President, the process will rarely be initiated for political reasons. 61 See Katy J. Harriger, Who Should Decide? Constitutional and Political Issues Regarding Section 4 of the Twenty-Fifth Amendment, 30 Wake Forest L. Rev. 563, 566 (1995).

At the same time, the process is not completely immune to politicization. As Tom Wicker notes, for section four to work, “everyone involved has to act honorably and with selfless disregard for his or her own personal or political interest.” 62 Tom Wicker, The Imperfect but Useful Twenty-Fifth Amendment, in Managing Crisis: Presidential Disability and the Twenty-Fifth Amendment 215, 216 (Robert E. Gilbert ed., 2000). Yet, the Vice President’s and principal officers’ partisan overlap with and personal loyalties to the President, while likely to prevent improper use of section four against the President, could tip the scale perversely in favor of nonuse. 63 See id. at 216-17; Harriger, supra note 61, at 578; see also Michael D. Shear & Shane Goldmacher, Team of Rivals? Biden’s Cabinet Looks More Like a Team of Buddies, N.Y. Times (Dec. 9, 2020), https://perma.cc/Y3UG-7H6T. But see Brian C. Kalt, The Many Misconceptions About Section 4 of the Twenty-Fifth Amendment, 47 Ohio N.U. L. Rev. 345, 355 (2021) (“To the framers, this was a feature, not a bug.”). Of course, section four does provide an alternative route: the creation of an “other body” by Congress. What this could possibly entail, however, is anyone’s guess. Some have suggested a panel of medical experts who would base their decisions upon physical and medical evaluations of the President. 64 See, e.g., Wicker, supra note 62, at 218; Harriger, supra note 61, at 580-83. As discussed in Part III below, this could be a sensible approach (though not without its downsides). 65 See infra Part III.B.2. Nevertheless, the broad language of “other body” suggests that Congress could also create an internal body composed of its own members with the authority to issue a written declaration under section four. The section thus leaves Congress with the opportunity to undermine the default checks and balances that exist within section four by transferring the bulk of the process over to the legislative branch.

Another strength of section four is its seeming preservation of the Office of the President’s democratic legitimacy. On its face, stripping an elected President of their power would appear to subvert the voters’ prerogative. 66 U.S. voters are not, of course, constitutionally entitled to choosing the President. See U.S. Const. art. II, § 1, cl. 2; id. amend. XII (outlining the electoral college). As of 2023, though, each state and the District of Columbia selects their electors by popular vote. See The Electoral College, Nat’l Conf. of State Legislatures, https://perma.cc/3WWZ-LUKP (last updated Mar. 21, 2023). Section four, however, has numerous features that help assuage this concern. For one, the President is given the chance to issue a written declaration to prove that they are in fact capable of performing their duties. Moreover, even if the President loses their power, said power transfers to the Vice President, who is also democratically elected. Lastly, section four’s wording makes it clear that, even if two-thirds of both congressional chambers were to determine that the President is too incapacitated for office, the Vice President still only becomes “Acting President.” As Joel Goldstein emphasizes, “the President remains President,” even if only in name. 67 Goldstein, supra note 45, at 123. This crucial distinction keeps the door open for the President to rechallenge a finding of incapacity and force the Vice President, the principal officers (or other body), and Congress to vote again on the issue, 68 See id. (“[T]he President can make repeated declarations that ‘no inability exists’ and can ‘resume the powers and duties of his office’ either upon subsequent acquiescence by the Vice President and Cabinet or if less than two-thirds of either House vote her disabled within twenty-one days.”). meaning the voters’ choice will never be wholly disturbed by the section-four process.

This “preservation” is not without its deficiencies, though. For instance, the process is still largely undemocratic in that the people have little, if any, say in it. While Congress is certainly composed of representatives of the people, it is still ultimately a body of only 535 individuals speaking on behalf of 330 million. Misalignment is bound to occur. 69 See Lee Drutman, Jonathan D. Cohen, Yuval Levin & Norman J. Ornstein, Am. Acad. of Arts & Scis., The Case for Enlarging the House of Representatives 12-14 (2021), https://perma.cc/5ZHJ-QCJP (noting how more populous districts lead to weaker connections between elected representatives and their constituencies). Furthermore, aside from the Vice President, the other decisionmakers in this process—namely the principal heads of the executive departments—are entirely unelected and unbeholden to the voting-age population. And any “other body” formed by Congress would likely be no different in this regard. If maintaining democratic legitimacy were thus a goal of section four, 70 Cf. Goldstein, supra note 60, at 1027 (“Cabinet member[s] may lack the democratic pedigree that the Twenty-Fifth Amendment envisions for a presidential successor.”). it may well have benefited from a more direct means of including the will of the people in the process, e.g., by involving state legislatures. 71 Cf. U.S. Const. art. V (involving state legislatures in the process of amending the Constitution); see also infra Part III.B.1.

Finally, section four is filled with vague language that has sparked numerous debates over its framers’ intentions. This is not always a defect. For instance, the ambiguous language of “unable to discharge the powers and duties” was no accident; rather, as Goldstein notes, it was “deliberate and represented a preference for flexibility and a faith in future decision-makers.” 72 Goldstein, supra note 45, at 78, 98-103. Perhaps one could argue that this gives too much leeway to the Vice President and principal officers in the process. Yet, imagine if, in the alternative, section four had been written to only cover physical disabilities or certain specific illnesses. Would conditions such as dementia have been covered? Or mental disorders that have received greater recognition by psychologists since 1967? Alternatively, would conditions that are no longer perceived as problematic as they were back in the day still be included within section four’s reach? Section four’s adaptable incapacitation standard may indeed be one of its greatest triumphs.

Naturally though, not all ambiguities are cause for celebration. As mentioned earlier, it is unclear what might qualify as an “other body”—the plain language would suggest it includes anything that Congress could possibly think up, though this seems quite extreme. Could the decision to transmit a written declaration be left up to the Vice President and, say, just one other assigned person? As unlikely as this is to happen, 73 Not only is Congress unlikely to create such an absurd “other body” for section-four purposes, but any such law creating said body would also need approval from the President per the requirements of bicameralism and presentment. See INS v. Chadha, 462 U.S. 919, 954-55 (1983). the sheer possibility is concerning. Section four also never fully defines “principal officers of the executive departments.” Many automatically assume this means Cabinet members, but this is not entirely certain. In fact, legislative history suggests that acting heads of departments could also be included in the decision-making process. 74 Harold Hongju Koh, Interpreting the Twenty-Fifth Amendment: Major Controversies, 10 ConLawNOW 263, 266-67 (2019). Unfortunately, only a crisis of incapacitation will force us to fully reckon with the precise meaning of this language.

Overall, the Twenty-Fifth Amendment presents us with several learning opportunities regarding how to adequately address congressional incapacity. Part III takes this guidance and attempts to provide a robust solution that adopts the Twenty-Fifth Amendment’s strengths while avoiding its shortcomings.

III. The Congressional Incapacity Amendment

As the problem of congressional incapacity faces increasing scrutiny, there is no greater time than now to address it head-on. As overviewed above in Part II, when concerns arose over the lack of any means of dealing with presidential incapacity, Congress and the state legislatures managed to pass and ratify the Twenty-Fifth Amendment within a matter of a few years. Similar action should now be taken to institute a congressional incapacity amendment.

At the outset, some may question whether the solution must be an amendment. The answer, nonetheless, is very likely yes. Indeed, the Constitution expressly grants Representatives and Senators two- and six-year terms, respectively. 75 U.S. Const. art. I, § 2, cl. 1; id. amend. XVII. At the same time, it contains no mechanism for a Representative or Senator to temporarily transfer the duties of their office, nor does it provide a way for involuntary revocation of their office beyond the Expulsion Clause. The Supreme Court has previously held statutes imposing term limits on congressional seats to be unconstitutional, finding that they “effect a fundamental change in the constitutional framework” and thus require adoption “through the amendment procedures set forth in Article V.” 76 U.S. Term Limits, Inc. v. Thornton, 514 U.S. 779, 837 (1995). Similarly, then, any attempt to resolve congressional incapacity in a way that alters the constitutionally established term length of a Senator or Representative would likely be found to require a constitutional amendment. 77 Further textual arguments could be made to support this conclusion. For instance, the Constitution seemingly restricts House and Senate membership to those elected. See U.S. Const. art. I, § 2, cl. 1 (“The House of Representatives shall be composed of Members chosen every second Year by the People . . . .”); id. amend. XVII (“The Senate of the United States shall be composed of two Senators from each State, elected by the people thereof . . . .”).

The amendment process admittedly presents great barriers, especially in today’s polarized political environment. It should not, however, totally dissuade action. For one, polls suggest strong bipartisan concern over the impact of our aging Congress on the body’s ability to properly govern. 78 See Madeline Halpert, Bipartisan Majority of Americans Believe in Age Limits for Elected Officials—and Most Think 80 Is Too Old—Poll Finds, Forbes (Sept. 8, 2022, 9:36 AM EDT), https://perma.cc/U7HL-V6DJ. Furthermore, fractured politics has historically been followed by waves of constitutional changes throughout U.S. history. 79 John F. Kowal & Wilfred U. Codrington III, The People’s Constitution: 200 Years, 27 Amendments, and the Promise of a More Perfect Union 6-8 (2021). Finally, we have already seen some movement in Congress in the past to address incapacity, even if only mass incapacitation. 80 For instance, in the wake of the September 11th terrorist attacks, Senator John Cornyn proposed an amendment providing procedures for a scenario in which one-fourth of either chamber were killed or incapacitated. See S.J. Res. 23, 108th Cong. (2003). Accordingly, this Part attempts to outline what a potential congressional incapacity amendment could look like. Specifically, it suggests sections to address both interim incapacitation that necessitates a temporary and voluntary transfer of congressional duties 81 This Essay uses the term “duties” rather than “powers” regarding members of Congress because the Constitution vests legislative powers to Congress as an institution rather than to its individual members. See supra notes 49-50 and accompanying text. and indefinite incapacitation that may require a more involuntary means of transfer. Example drafts of such sections are provided along the way.

A. Voluntary, Interim Transfer of Duties

The congressional incapacity amendment should begin by providing a mechanism for Senators and Representatives to relinquish their office to a temporary appointee in cases of short-term incapacity, such as emergencies or anticipated medical procedures. As of now, members of Congress will sometimes go months without actively performing their congressional duties while recovering from a stroke, a heart attack, or any other number of physical or mental ailments. 82 See supra note 20 and accompanying text. No one should feel shame for enduring such hardships, of course. Life happens. Nevertheless, members should feel comfortable taking the time they need without worrying about their office being neglected. More importantly, to maintain the principles of our democratic system of government, constituents deserve continued representation at all times in Congress.

This hypothetical amendment’s first section should therefore partially mirror section three of the Twenty-Fifth Amendment: When a member of Congress expects that they will be unable to fulfill their role for a finite period of time, they should have the option to present a written declaration indicating so, at which time their duties can temporarily transfer to an “acting” Senator or Representative. To whom would they send this written declaration? Section three of the Twenty-Fifth Amendment has the President send theirs to the Speaker of the House and the Senate’s President pro tempore. While ultimately insignificant, this arrangement produces a sense of checks and balances between the two political branches worthy of replication. Accordingly, Senators and Representatives could send their respective written declarations directly to the President or Vice President, the latter of whom may be a good choice given their more direct involvement with Congress. 83 See U.S. Const. art. I, § 3, cl. 4 (“The Vice President of the United States shall be President of the Senate . . . .”). Alternatively, Representatives could send their written declarations to the President pre tempore while Senators send theirs to the Speaker of the House. The ultimate recipient is not particularly important so long as they are another accountable public official. Furthermore, for reasons outlined in the next couple paragraphs, copies should also be sent to the governor of a Senator’s or Representative’s state.

At this point, section three loses its instructive purpose, as Senators and Representatives have no pre-selected stand-in akin to the Vice President waiting to take the reins. Fortunately though, there is some constitutional precedent off which to build, in that the Seventeenth Amendment permits state governors to “make temporary appointments” in the event of the death or resignation of a Senator. 84 Id. amend. XVII. Nevertheless, vacancies in the House of Representatives must be filled by election only. See also id. art. I, § 2, cl. 4 (“When vacancies happen in the Representation from any State, the Executive Authority thereof shall issue Writs of Election to fill such Vacancies.”). As of today, forty-six states allow their governors to make interim appointments for Senate vacancies, with varying degrees of additional requirements, such as mandating special elections following the appointment. 85 Nat’l Conf. of State Legislatures, supra note 41. While some may criticize particular appointments, this practice has proven crucial overall in helping the Senate continue its work without the disruption of a vacancy. 86 See, e.g., Justin Sink, Former Rep. Barney Frank Wants Interim Appointment to Replace Kerry in Senate, The Hill (Jan. 4, 2013, 1:15 PM ET), https://perma.cc/ZM8T-WJXK (“Frank said he wanted the appointment so that he could serve during looming negotiations on the debt ceiling and sequester.”); see also Louis Jacobson, Gubernatorial Appointment Powers for U.S. Senate Seats: Which Vacancies Could Prompt a Party Switch?, Univ. of Va. Ctr. for Pol. (Apr. 30, 2020), https://perma.cc/3UHS-9YSB. The congressional incapacity amendment could thus incorporate this same process into its first section to determine who temporarily assumes the office of a Senator or Representative in the case of an interim transfer of duties.

Naturally, a question arises as to whether it would be proper for a statewide official to appoint an interim Representative when, in most states, House districts only constitute a portion of the given state. Perhaps the best justification for leaving the decision in the hands of the governor though is that House districts typically contain multiple counties, cities, or other localities. Moreover, many such localities end up split between multiple districts. Consequently, no local executive would seemingly have a more legitimate claim over the appointment of an interim Representative than would a governor. Still, to quell concerns, this section could authorize state legislatures to institute an alternative means of appointment if they so desire. Furthermore, interim Representatives could be required to reside within the district they would be serving, thus forcing a governor to take more localized considerations into account upon making an appointment.

87

Representatives are currently not constitutionally required to reside within their district, but instead need only inhabit “that State in which [they] shall be chosen.” U.S. Const. art. I, § 2, cl. 2. Nevertheless, with single-member districts now being ubiquitous, see 2 U.S.C. § 2c (2018) (mandating single-member districts), voters have come to expect their Representative to live within their district. See, e.g., Tia Mitchell, 4 of 14 Georgia Members of Congress Live Outside Their Districts, Atlanta J.-Const. (Jan. 30, 2023), https://perma.cc/7QWE-BDYS. Accordingly, requiring interim Representatives to reside within the district they would temporarily serve, while not a prerequisite for actual Representatives, would incorporate voters’ modern understanding of how representation in the House should operate.

One final apprehension that voters and members of Congress may have with this process is the potential scenario in which an interim appointee is of a differing political party. Interestingly, the Seventeenth Amendment makes no mention of party in its provision on appointees. Yet, numerous states have independently passed laws compelling governors’ interim Senate appointees to be of the same political party as the Senator vacating the seat.

88

See, e.g., Ariz. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 16-222(C) (2023); Ky. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 63.200(1)(b) (West 2023); Md. Code Ann. Elec. Law § 8-602(a)(1)(iii) (West 2023).

This section could adopt this feature and require appointees to share political party affiliation with the incapacitated member whose role they are assuming. Alternatively, though perhaps a more dramatic move, the section could enable Senators and Representatives to themselves select a slate of potential appointees from which the governor must choose. Similar proposals have been made to address mass incapacitation,

89

See, e.g., Am. Enter. Inst., supra note 12, at 3 (“Members designating their own successors would ensure that the replacement member would be most likely to carry on the representation of the deceased member.”).

and such a system would prevent instances such as, say, a progressive Democrat worrying about a Republican governor selecting a conservative Democrat as a temporary appointee (and vice versa). Such a slate would ideally be selected prior to an election for any given term—almost akin to running with designated “Vice” Senators or Representatives—that way voters have a chance to know who could potentially take over the role during said term.

With all this said, section one for this hypothetical congressional incapacity amendment could read as follows (with some alternative or interchangeable text placed in brackets):

Whenever a Senator or Representative transmits to the [President / Vice President] his or her written declaration that he or she is unable to discharge the duties of his or her office, and until he or she transmits to the [President / Vice President] a written declaration to the contrary, such duties shall be discharged by a temporary appointee.

The Senator or Representative shall also transmit a copy of the written declaration to the executive of the State of the Senator or in which the Representative’s district resides. Said executive shall make the temporary appointment[, unless the legislature thereof prescribes an alternative method of choosing a temporary appointee]. All temporary appointments must be made within seven days of the executive’s receipt of the written declaration.

Temporary appointees must [share the same political party affiliation, if any, of the Senator or Representative at the time of transmission of the written declaration / be selected from a list of five potential appointees designated by the Senator or Representative prior to their election to their current term]. Temporary appointees for Representatives must reside within said Representative’s district at the time of appointment.

With voluntary interim transfers of duties handled, the amendment’s next section would, perhaps more controversially, cover involuntary transfers.

B. A. Involuntary Transfer of Duties

The second section of the congressional incapacity amendment should be comparable to section four of the Twenty-Fifth Amendment, providing a remedy for situations in which a Senator or Representative can no longer adequately perform their duties but is unable or unwilling to transfer them via section one. 90 See, e.g., supra notes 21-22, 42 and accompanying text (Senators Cochran, Feinstein, and Thurmond). Nevertheless, as noted above, it should be written to include the strengths of section four of the Twenty-Fifth Amendment while avoiding its drawbacks. 91 See supra Part II.B. This section should therefore be multi-layered, involving multiple branches of government. At the same time, the involved bodies should be composed of officials in a position to exercise more independent judgment than, say, the Vice President and principal officers in the context of presidential incapacity. This section should also strive to maintain the democratic legitimacy of Congress while also ensuring that the people have a more direct say in the process than exists in section four of the Twenty-Fifth Amendment. Finally, the section should use ambiguous language only when beneficial, and not to the detriment of establishing a clear process.

With this in mind, this Essay suggests that the decision to initiate the process of involuntary transfer of a Senator’s or Representative’s office should be left not to any federal body, but instead to the affected constituents, either through direct vote or by proxy via state legislatures. Furthermore, similar to how section four of the Twenty-Fifth Amendment involves the participation of the President’s colleagues, this hypothetical section two of the congressional incapacity amendment should involve Congress, though perhaps only indirectly to avoid any personal or political pressures obscuring objective decision-making. To accomplish this, this Essay proposes the creation of a permanent “other body” of licensed medical practitioners—appointed by Congress—to provide the final vote on a Senator’s or Representative’s ability to perform their duties. Naturally, one could raise many criticisms about this process, which this Essay does its best to recognize and address below.

1. Initiation by the People

When members of Congress are unable to properly serve, their constituents are arguably the most directly impacted group. 92 Such a scenario conflicts with the old democratic precept: No governance without representation. See John Locke, Two Treatises of Government § 140 (Peter Laslett ed., rev. ed. 1963) (“‘Tis true, Governments cannot be supported without great Charge . . . . But still it must be with . . . the Consent of the Majority, giving it either by themselves, or their Representatives chosen by them.”); see also supra Part I.B. It stands to reason then that, if we were to involve the people more in this process than the Twenty-Fifth Amendment does, the constituents should be the ones to initiate it. There are a couple of ways to do this. The most unadulterated would be through a direct vote, either statewide for Senators or districtwide for Representatives. Some may (fairly) characterize such votes as recalls. Recalls have both upsides and downsides associated with them. As some commentators note, the lack of a recall option for members of Congress insulates them from constituent preferences. 93 See Jonathan S. Gould, The Law of Legislative Representation, 107 Va. L. Rev. 765, 792-93 (2021). Yet, as one scholar observes, this insulation helps protect members “from immediate passions and interests” that might disrupt deliberative lawmaking. 94 Vicki C. Jackson, Pro-Constitutional Representation: Comparing the Role Obligations of Judges and Elected Representatives in Constitutional Democracy, 57 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 1717, 1745-46 (2016). In light of this lack of consensus over the merits of recalls, the best argument against a direct vote may instead pertain to its feasibility. Organizing a referendum is a time-consuming endeavor, often requiring tens, if not hundreds, of thousands of signatures. 95 See Signature Requirements, Ballotpedia, https://perma.cc/Z6TJ-YYVA (archived July 27, 2023). And if a vote were to happen, it would require a substantial amount of money and labor to carry out. 96 See, e.g., John Myers, California Recall Election Cost $200 Million, Officials Say, L.A. Times (Feb. 3, 2022, 6:00 PM PT), https://perma.cc/3JC2-WE7L. Such timelines and costs might not be conducive to a situation like congressional incapacitation that necessitates more immediate action.

A more workable substitute for direct votes could be state legislatures. The Constitution already incorporates state legislatures into multiple processes—e.g., the regulation of congressional elections, the choosing of electors, and the ratification of amendments—seemingly as a proxy for the will of the people of each given state. 97 See U.S. Const. art. I, § 4 (Elections Clause); id. art. II, § 1, cl. 2 (Electors Clause); id. art. V (amendment process); see also Corinna Barrett Lain, The Doctrinal Side of Majority Will, 2010 Mich. St. L. Rev. 775, 776 (noting that the Supreme Court views state legislatures as a “proxy for the will of the people”); Jacob Lemon-Strauss, Note, The States Are Right: Arguing for the Continued Use of State Legislatures in Forming a National Consensus for the Evolving Standards of Decency, 47 Am. Crim. L. Rev. 1319, 1325 (2010) (describing state legislatures as “moral prox[ies] for the people”). State legislatures will never, of course, perfectly align with the desires of those they represent. Nevertheless, almost all state legislators (with the exception of state senators in California and Texas) serve fewer constituents than the average member of the House of Representatives. 98 Compare Sarah J. Eckman, Cong. Rsch. Serv., R45951, Apportionment and Redistricting Process for the U.S. House of Representatives 2 (2021), https://perma.cc/NX56-ZV2Z (“The average congressional district population for the United States following the 2020 census was 761,169 individuals.”), with Population Represented by State Legislators, Ballotpedia, https://perma.cc/7RAP-62Y9 (archived July 27, 2023) (showcasing how most state legislators serve far fewer than 761,169 individuals). Accordingly, the congressional incapacity amendment could entrust state legislatures with the responsibility of issuing a written declaration—preferably through a supermajority vote—that a Senator or Representative is unable to discharge their duties. 99 Again, one could question why a state’s entire legislature should have the authority to initiate this process against a Representative serving a district that encompasses only a portion of the state. Nevertheless, it is hard to imagine a more legitimate body to hold this power, given that districts are often composed of multiple counties, cities, and other localities. One might also note that many state legislatures operate part time or are only in session for parts of the year. Yet, special sessions could presumably be called for a matter of great important such as congressional incapacity. See 2023 State Legislative Session Calendar, Nat’l Conf. of State Legislatures, https://perma.cc/2QZK-W6HK (last updated July 19, 2023).

Next, similar to section one, the state legislature’s written declaration could be transmitted to the executive branch and the relevant governor. Once this happens, the governor of the Senator’s or Representative’s state could make a temporary appointment in the same manner, and subject to the same constraints, as suggested for voluntary transfers in section one—e.g., having to be a member of the same political party or having to be chosen from a pre-designated slate of potential appointees. Then, like the President under the Twenty-Fifth Amendment, the Senator or Representative would be given the opportunity to issue a responding written declaration to the executive branch and governor that defends their capacity to serve.

Should this happen, there are multiple ways to potentially go about the next step. One possibility is that the group that initiated this process—e.g., the state legislature—would again need to transmit a written declaration to trigger a final decision on whether the Senator or Representative should be stripped of their official duties. This would mirror how section four of the Twenty-Fifth Amendment requires the Vice President and principal officers/other body to again vote on the President’s incapacity. Nevertheless, one of the ultimate benefits of involving the Vice President and principal officers in the decision is that it recognizes and incorporates the institutional interest of the executive branch. Thus, an alternative possibility could be to give Congress itself—or the relevant chamber—the power to transmit the second written declaration that triggers the final decision. The downside of this would be that it would somewhat replicate the already existing Expulsion Clause process, arguably rendering the congressional incapacity amendment a constitutional redundancy. It would also inject the same conflict-of-interest problem into the process that exists in section four of the Twenty-Fifth Amendment.

Regardless of which body transmits the second written declaration, the final decision should not be made by the executive branch, as resting this decision in the hands of the President would implicate serious separation-of-powers concerns. Nor should it go directly to Congress, given its members’ conflicts of interest. Instead, as the next section covers, the decision should fall to a clearly defined “other body” with the ability to exercise independent and informed judgment on the status of the Senator’s or Representative’s physical and mental capabilities.

2. Congressional Medical Oversight Board

The final decision of this process should be made by a body that can engage in objective judgment. While one could imagine many potential contenders for this role, this Essay puts suggests a Congressional Medical Oversight Board (“Board”), composed of licensed medical practitioners. This concept is not entirely out of left field. Indeed, multiple scholars have pondered the use of medical experts in the context of section four of the Twenty-Fifth Amendment. 100 See, e.g., Wicker, supra note 62, at 218; Harriger, supra note 61, at 580-83. And with good reason, as many of the weaknesses of section four could be avoided with such a Board. 101 See supra Part II.B. For one, there would no longer be any vague “other body” possibilities. 102 See supra notes 64-65, 73-74 and accompanying text. More importantly though, risks of overly subjective or self-serving decision-making would wane, as the Board would be swayed less by the personal or political implications of their decision than would be Congress or officers of the executive branch, all while possessing far greater knowledge on what actually constitutes inability. 103 Not all instances of incapacity will involve medical debilitation, of course. Nevertheless, any other types of incapacitation—e.g., disappearance—would likely be even more clear-cut than anything medical-related and therefore easy for the Board to ascertain and make a decision on.

This Board would by no means be a perfect option, of course. After all, doctors are still human beings subject to political biases, even if not driven by personal relationships with politicians. 104 See Janet Adamy & Paul Overberg, Doctors, Once GOP Stalwarts, Now More Likely to Be Democrats, Wall St. J. (Oct. 6, 2019, 1:38 PM ET), https://perma.cc/V5N7-3JXX. Moreover, being unelected, the Board would still pose issues of democratic legitimacy. Finally, the public, high-stakes nature of the position could make it difficult to even find doctors willing to serve on the Board. As Katy Harriger points out, such a Board may be subject to “the Freedom of Information Act, Government in the Sunshine Act, and Ethics in Government Act,” 105 Harriger, supra note 61, at 582; see also Wicker, supra note 62, at 218 (“[T]he panel could be subject to scary publicity and/or malicious or inaccurate ‘leaks’ . . . .”). which could scare away potential candidates who value their privacy.

One possible way to alleviate these issues would be to give Congress some degree of involvement in the selection and regulation of the Board. This would ensure some democratic accountability over the selection of Board members. Furthermore, to reduce the threat of partisan decision-making, one-third of the Board could be selected by Democratic members of Congress, one-third by Republican members, and the remaining one-third jointly. 106 Cf. 15 U.S.C. § 41 (2018) (“Not more than three of the [FTC] Commissioners shall be members of the same political party.”). This arrangement, combined with a requirement that the Board must reach a supermajority decision to transfer official duties away from a Senator or Representative, would prevent decisions from being made to advantage any political party. Lastly, the congressional incapacity amendment could grant Congress the ability to make rules as needed to ensure that the Board is able to be staffed and function properly, such as putting safety measures in place to protect Board members from harassment.

Once the Board votes that a Senator or Representative is unable to discharge their duties, the temporary appointee would continue to serve as an acting member of Congress. The Senator or Representative would be free to rechallenge such a decision within their term and restart the process, though they would not reassume their duties unless a supermajority vote could no longer be reached at any step along the way (e.g., by the state legislature or the Board). Thus, the voters’ choice of Senator or Representative is never fully revoked, all while their representation goes undisrupted.

3. Potential Text

Incorporating all that has been said thus far, section two of the congressional incapacity amendment could read as follows:

Congress shall create a Congressional Medical Oversight Board within one year of the ratification of this amendment. The Board shall comprise nine licensed physicians, each of whom shall serve on the Board for ten-year terms upon appointment and serve no more than two terms total. Congress shall also create a Joint Committee, comprising an equal number of congresspersons from the two most represented political parties in Congress, that will be tasked with appointing members to the Board. Both party caucuses within the Joint Committee shall each appoint three Board members with two-thirds approval of the respective caucus. The remaining three Board members shall be appointed with two-thirds approval of the Joint Committee at large. The Joint Committee shall issue rules deemed necessary to facilitate this process. No Board seat shall go vacant for more than one year.

Whenever two-thirds of each house of a State legislature transmits to the [President / Vice President] and executive of the State its written declaration that a Senator or Representative of the State is unable to discharge the duties of his or her office, the executive thereof shall within seven days choose a temporary appointee to assume the duties of the office, provided the appointee conforms with the requirements of section one of this amendment. Thereafter, whenever the Senator or Representative transmits to the [President / Vice President] and State executive his or her written declaration that no inability exists, he or she shall resume the duties of his or her office unless two-thirds of [each house of the aforementioned State legislature / each chamber of Congress / the chamber of the Senator or Representative] transmits within seven days to the Board its written declaration that the Senator or Representative is unable to discharge the duties of his or her office. Thereupon the Board shall assemble within forty-eight hours and decide the issue. If, after twenty-one days, the Board determines by two-thirds’ vote that the Senator or Representative is unable to discharge the duties of his or her office, the temporary appointee shall continue to discharge the same; otherwise, the Senator or Representative shall resume the duties of his or her office.

As with any calls to constitutionally alter our democratic system, this hypothetical section will evoke pushback. This Part thus concludes by briefly addressing a few potential criticisms (beyond those already addressed throughout above).

4. Potential Criticisms

In addition to the concerns addressed throughout this Essay, some may have more general criticisms of the congressional incapacity amendment, at least as I have pitched it. For one, there is the ever-present challenge of politicization. Some degree of political calculus is, of course, inevitable in processes that transfer duties from one official to another. Nevertheless, one could argue that giving, say, state legislatures the ability to initiate a congressional ousting is an absolute recipe for partisan disaster, especially in scenarios in which a state legislature’s controlling party differs from that of the incapacitated congressperson. I would only say that such scenarios can be largely avoided by imposing a high enough voting threshold, such as two-thirds as suggested in the hypothetical section above. Given that there are very few states in which the legislature is controlled two-to-one within each house by a party different than that of a sitting member of Congress from said state, 107 Compare Nat’l Conf. of State Legislatures, 2023 State & Legislative Partisan Composition (2023), https://perma.cc/RCY7-J2TH, with Members of the U.S. Congress, U.S. Cong., https://perma.cc/BW5C-9DYM (archived Aug. 3, 2023). this supermajority requirement would all but force bipartisan agreement. 108 It should also be noted that while state legislatures’ members may be more polarized than those of Congress, state legislatures ultimately act in a less polarized manner than Congress. See State Legislative Policymaking in the Age of Political Polarization, Nat’l Conf. of State Legislatures, https://perma.cc/YQ3L-TKLM (last updated Feb. 1, 2018) (“[M]ost of the legislatures in our sample were able to negotiate differences and reach settlements on major policy issues . . . under conditions of political polarization and divided government.”). And even if a state legislature occasionally managed to transmit a written declaration for improper reasons, the additional bodies involved in the process—the Board and potentially Congress—would act as a check on this decision.

Conversely, others might find it inappropriate for nonpolitical figures like doctors to have substantial say in what is, as Harriger puts it, “an essentially political decision with profound consequences in a constitutional democracy.”

109

Harriger, supra note 61, at 583.

To begin, I would disagree with this characterization. The Board would not be engaging in a political decision, but rather a professional decision with a political outcome. To some, this may be a distinction without a difference. At the same time, the involuntary transfer process I have proposed would hardly lack the influence of political bodies, be it the state legislatures issuing the initial written declaration, the Senator or Representative providing their own counter-declaration, Congress potentially issuing the second written declaration, or Congress being in charge of appointing doctors to the Board. The Board itself would be only one part of the process, even if an important one.

Relatedly, regarding the actual feasibility of passing this amendment, some may argue that Congress would never allow its members to be subject to the decision of the Board. Yet, elected officials have routinely supported and adopted constraints on their own officeholding, such as term limits and campaign finance laws,

110

Indeed, even members of today’s Congress have continued to call for congressional term limits and increased campaign finance regulation. See, e.g., Press Release, Sen. Ted Cruz, Sen. Cruz Introduces Constitutional Amendment to Impose Term Limits for Congress (Jan. 23, 2023), https://perma.cc/6DHV-9M2Y; Press Release, Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse, Whitehouse, Cicilline Reintroduce DISCLOSE Act to End Corrupting Influence of Dark Money in American Democracy, (Feb. 17, 2023), https://perma.cc/E27Q-4JLY.

and have likewise voluntarily subjected themselves to external decision-making bodies, e.g., the Federal Election Commission. While the proposed Board would certainly wield far more influence than a civil enforcement agency, these examples still show that there is an appetite among our federal legislators for placing restrictions on their own power.

Beyond politicization, some may view it as undemocratic to ostensibly remove an elected official from office before they finish out their term. This ultimately ends up becoming a balancing act. Yes, elected officials should ideally remain serving their constituents for the term to which they were elected. At the same time, if an official is unable to truly represent those constituents, said constituents will essentially go unseen within the democratic system. The best compromise is thus to maintain, to the maximum extent possible, the will of the people throughout the involuntary transfer process. This is why I have recommended involving a vote reflecting said will, either directly or by proxy, at the outset of the process. 111 See supra notes 94-100 and accompanying text. Moreover, Senators and Representatives would always have the option during their term to issue another counter-declaration, forcing the involved bodies to reassess their incapacity. 112 Cf. supra note 68 and accompanying text. Finally, should the amendment be written to allow Senators and Representatives to designate a binding slate of potential temporary appointees prior to their election, 113 See supra note 90 and accompanying text. then any temporary appointees that do assume office would have in a sense already been chosen by the people.

Conclusion

The problem of congressional incapacity will continue, and likely escalate, in the coming years. Now is the time to resolve it by constitutional amendment. To be sure, implementing a new amendment is no easy task. Yet, if there were an amendment capable of achieving ratification these days, it would surely be one remedying the universally recognized issue of our federal elected officials being unable to fulfill their representative duties. This country has already instituted such an amendment for our President, thus providing us with a useful blueprint for how to proceed with a congressional incapacity amendment. And while this Essay does not purport to provide all the answers on how to best resolve congressional incapacity, I hope it at the very least sparks further discussion on the topic. Perhaps work could even be done to link solutions to the incapacity of individual members of Congress with that of mass congressional incapacitation. Americans deserve actual, functional representation in Congress. A congressional incapacity amendment would help ensure that each one receives it.

* Research Assistant Professor of Law, University of Virginia School of Law; Fellow, Karsh Center for Law and Democracy. Special thanks to Jerry Goldfeder, whose Just Security piece on this topic inspired me to write this Essay. See supra note 15. Thank you also to Joel Goldstein, Bertrall Ross, Richard Briffault, and Matthew Clifford for providing their invaluable thoughts on this topic. All errors are my own.